The Persistence of Conversion Therapy: Progressive Era Origins and the Creation of Ideal Citizens, 1900-1973

This article is authored by J. Seth Anderson, from the 2019-20 cohort of the LGBTQ Research Fellowship program at the One Institute.

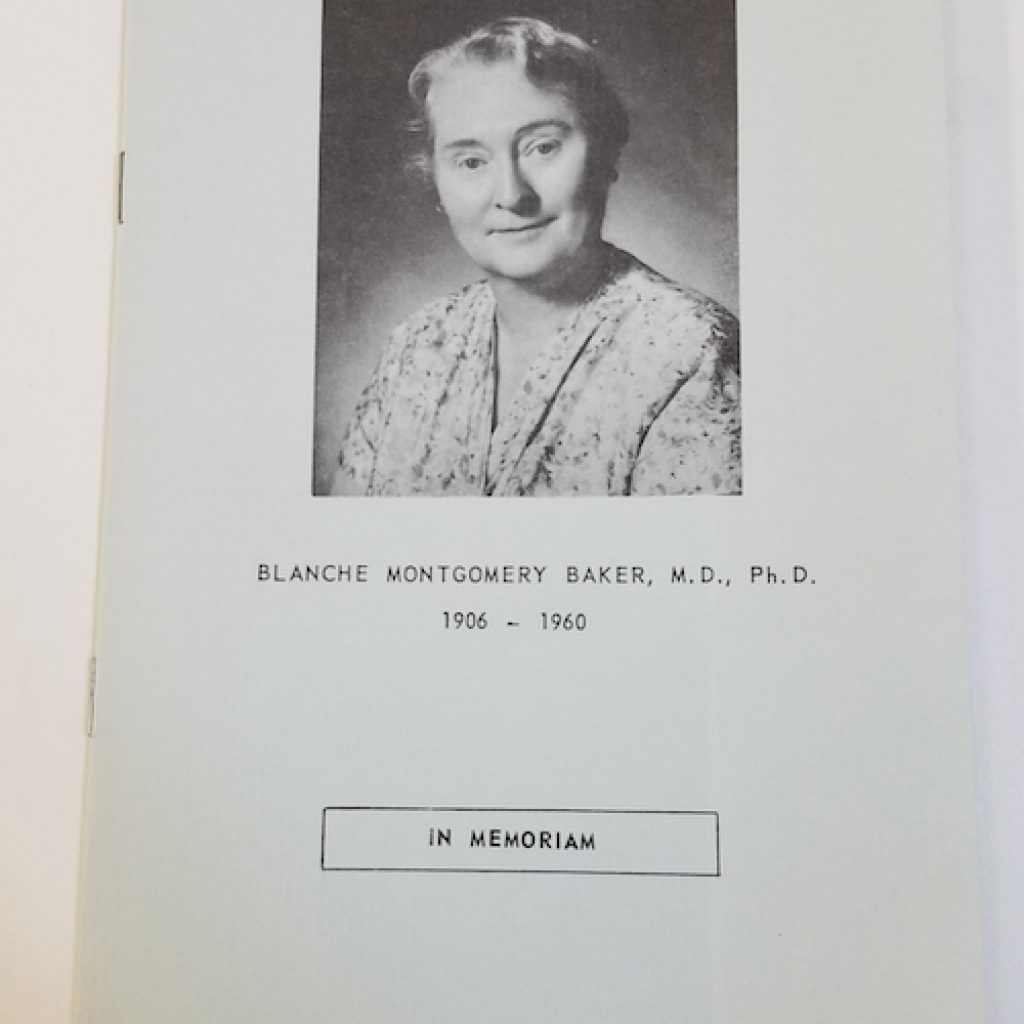

Thanks to the support of the One Institute LGBTQ Research Fellowship, I escaped the chilly Boston winter and found myself on a pilgrimage in sunny Los Angeles. I am a PhD candidate at Boston University and had the opportunity to spend time in the archive working on a dimension of my project related to the role of women psychiatrists in the development of what has come to be known as “conversion therapy,” the set of psychological and spiritual practices designed to change an individual’s sexual orientation from fundamentally homosexual or bisexual to fundamentally heterosexual. My project centers on the early developments of this set of practices, particularly on the people whose ideas resisted the emerging medical orthodoxies of their eras. Central to this story is how professional women pushed back against the idea that homosexuality was a mental illness. The name Evelyn Hooker might be familiar to many people, but there was another woman, Blanche Baker, a medical doctor and clinical psychiatrist who also used her professional credentials to position herself as an ally for gays and lesbians in the 1950s. From the ONE Inc. Records Collection, I gleaned a great deal of knowledge about Baker’s personhood, her practice, and her views on sexual orientation change efforts.

Born in 1906 in Columbus, Ohio, Baker grew up with parents who both valued education and encouraged her to read and think critically, even from an early age. She learned about homosexuality during her freshman year at Ohio State University in 1924, and on the suggestion of her father read the works of Havelock Ellis, one of the first doctors to write about homosexuality in the late nineteenth century. “Our early experiences always do put an indelible stamp upon us- we may change them to a certain extent, but I thank heaven I got a very broad viewpoint from the beginning and was able to understand [the topic of homosexuality],” she said in a speech in the 1950s. She completed her undergraduate work in biology, obtained her doctorate degree in abnormal psychology, earned a medical degree and specialized as a psychiatrist. Baker did not find persuasive the arguments that homosexuality was an illness that could be cured through psychiatric treatment or punished out of existence through confinement, and she directly expressed these views in her writings and speeches.

In late 1958, Baker began writing a column in ONE Magazine called “Toward Understanding” in which she answered letters from the mostly gay and lesbian readership and offered the perspective of a psychiatrist. The column was an instant success. “Dear Ann Landers of ONE Magazine,” began one letter she received from a reader in October 1959. In this collection I read a variety of unpublished letters, her correspondences with the editors of ONE, speeches, as well as several years of Christmas letters she sent to friends. Sadly, Baker died in December 1960 at the age of 54, which left me to wonder how sexual orientation change efforts might have developed in the 1960s had she lived through that decade of rapid social revolutions and been able to continue her challenge against the ascendant medical doctrines and practices.

In addition, I also spent time reading the Betty Berzon Collection, another woman whose work challenged the dominant medical perspectives about homosexuality and cures. In a speech given in 1980, Berzon recounted how she herself saw a therapist for eighteen years who tried to convince her she was not a lesbian. As a psychotherapist, Berzon organized the Gay Psychologists Association in the early 1970s, which helped gay and lesbian therapists’ network and assert themselves professionally. The practice of conversion therapy continued to spread in the 1970s and 1980s and Berzon’s career shows how she helped to resist it. To my surprise, I learned Berzon had been a student of Evelyn Hooker’s in the 1950s.

The week I spent at the ONE Archive helped me see more clearly how women doctors have long been on the forefront of rejecting the idea that homosexuality is a mental illness in need of a cure. I am grateful for the opportunity this fellowship allowed me to spend in the archive and I hope I can return soon.

J. Seth Anderson

2019 LGBTQ Research Fellow, One Institute