Safe Space for LGBTQ+ Expression

Young gay men began visiting the unofficial “gay beach” north of Santa Monica as early as 1940. This area of Will Rogers Beach, demarcated today by lifeguard towers 17 and 18, has become commonly known among the local LGBTQ+ community as “Ginger Rogers Beach,” a nod to the glamorous actress of Broadway and Hollywood fame. According to film professor David Lugowski, gay men were infatuated with Rogers’ campy talents, androgynous performances, and diva persona– so much so that drag queens began emulating her in the 1930s and 1940s, and continue to do so today.

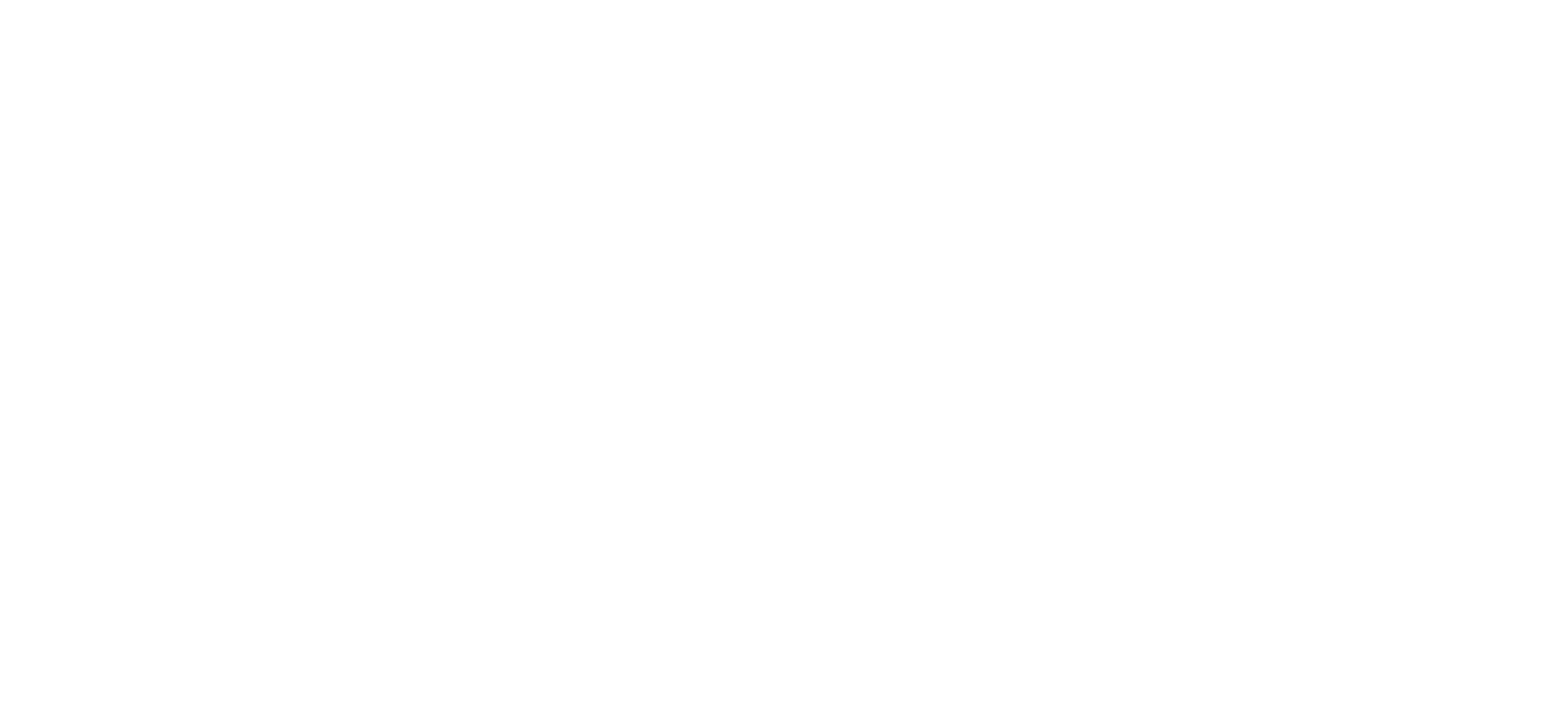

Image: Jim Kepner, “Santa Monica Beach,” from 132 Vignettes: A Suite for Lovers, Tricks, Fascinations & Near Misses, 1985-1990. Jim Kepner Papers, ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

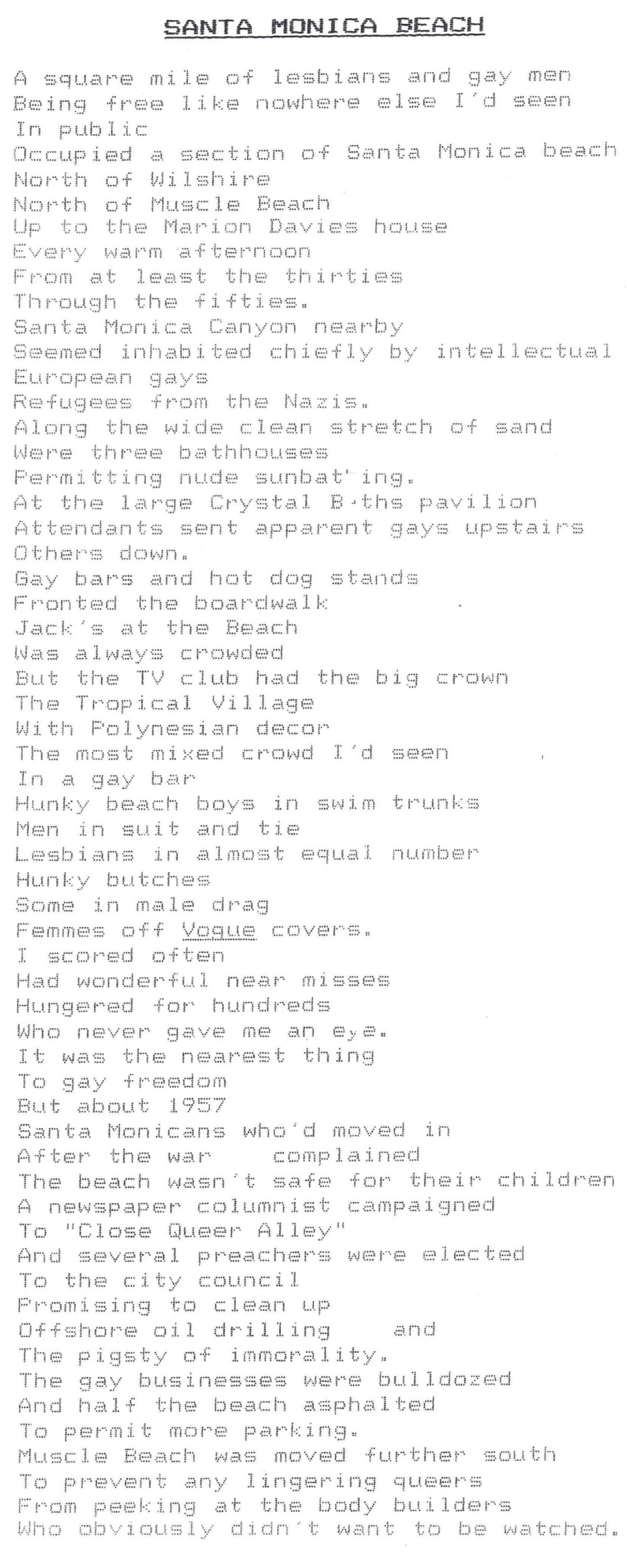

Image: “Pat Rocco relaxing at Santa Monica beach with friend,” undated. Pat Rocco photographs and papers, ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

WWII Migration

World War II catalyzed the growth of concentrated, under-the-radar gay communities in urban centers, especially port cities like Los Angeles as men and women embraced newfound economic opportunity and personal freedoms away from their home lives. More military personnel moved to Los Angeles than to any other city throughout the 1940s, and beaches served as a critical safe space for queer people.

In Gay L.A., Lillian Faderman and Stuart Timmons write: “For symbolic and functional reasons, the beach was especially attractive to gay people. It represented the very edge of the continent, far away from ‘back home’… During and after the war, veritable oases of gay life could be found in the open at many Los Angeles beaches, where the atmosphere was celebratory, carnival-like, even lawless.”

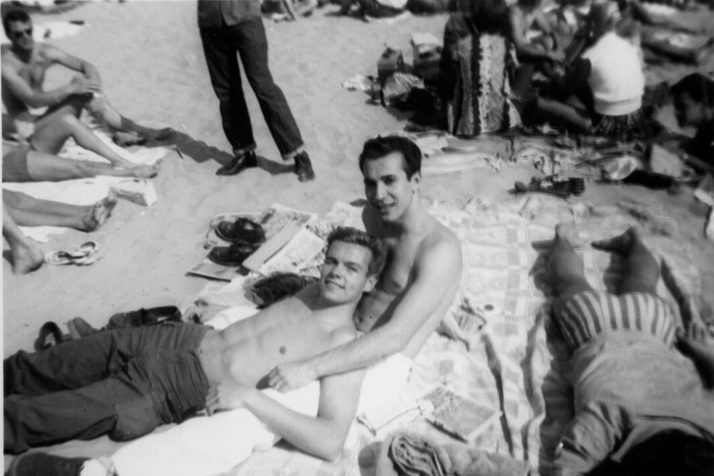

Image: “Colorized photo of José Sarria in his World War II uniform,” c. 1939-1945. Jose Sarria papers, courtesy of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Historical Society.

José Sarria Pays a Visit

As a teen in the 1950s, Faderman– the “mother of lesbian history”– observed gay people at the beach freely expressing their flamboyance and exploring romance. In the summer of 1957, Faderman and a crowd of gays watched San Fransico drag queen Jose Sarria give an impromptu performance on the sands.

Born in San Francisco in 1922 to a single mother from Colombia, José Julio Sarria put his plans to become a teacher on hold after high school and enlisted in the U.S. Army following the attack on Pearl Harbor. While stationed in Berlin, Sarria became infatuated with queer nightlife.

Sarria returned to San Francisco in 1947, receiving an honorable discharge. Shortly after, he was arrested by a vice officer and barred from pursuing a teaching license.

Sarria began waiting, hosting, and performing at the Black Cat Cafe in San Francisco, for which the Armed Forces Disciplinary Control Board had barred military personnel, perhaps ironically, drawing the attention of queer servicemembers.

After his vice arrest, Sarria vowed “to be the most notorious impersonator or homosexual or fairy or whatever you want to call me– and you would pay me for it.” Sarria took to the streets in drag in an open challenge to local morals statutes. He ran for a city supervisor’s seat in 1961, the first openly-LGBTQ+ person and drag queen to run for government office in the U.S. Later, as a founder and head of the Imperial Court System, Sarria created not only an oasis for gay pride and celebration, but a fundraising force for gay rights causes across the United States, casting him as a peerless leader in the early fight for gay rights.

Image: “Mattachine Society founders at beach,” undated. Mattachine Society photographs (c. 1920-1952), ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

Mattachine Society

In 1950, Harry Hay and Rudi Gernreich gathered 500 signatures at Will Rogers State Beach for a petition opposing the Korean War and McCarthyism. At this time, gay beachgoers were not yet willing to join an organization to discuss homosexual rights.

In 1995, Hay wrote: “Forming a society of two, and determined to get a discussion group going, [Rudi and I] went to an unmarked section of Santa Monica Beach that we knew was frequented by gay brothers… By the end of the summer, we had gotten 500 signatures on our petition, and had found not one person who would dare come to our [homosexual] discussion group, so overpowering was the terror of police reprisal or blackmail.”

The following year, Hay led the formation of the Mattachine Society in Los Angeles, one of the nation’s first gay rights organizations. Mattachine argued that gay and lesbian people were a minority group oppressed by a prejudicial society and that they needed to organize in order to challenge their unjust persecution.

Membership in the organization grew slowly. At this time, most gays and lesbians believed that assimilation would be their best option and would not risk exposure for what they viewed as an impossible cause. In 1952, when the society successfully defended a police entrapment case against one of its founders, Dale Jennings, membership rapidly expanded with chapters forming across the United States. Members of Mattachine originated the idea of a national gay magazine, which later developed into ONE Magazine and ONE, Inc.

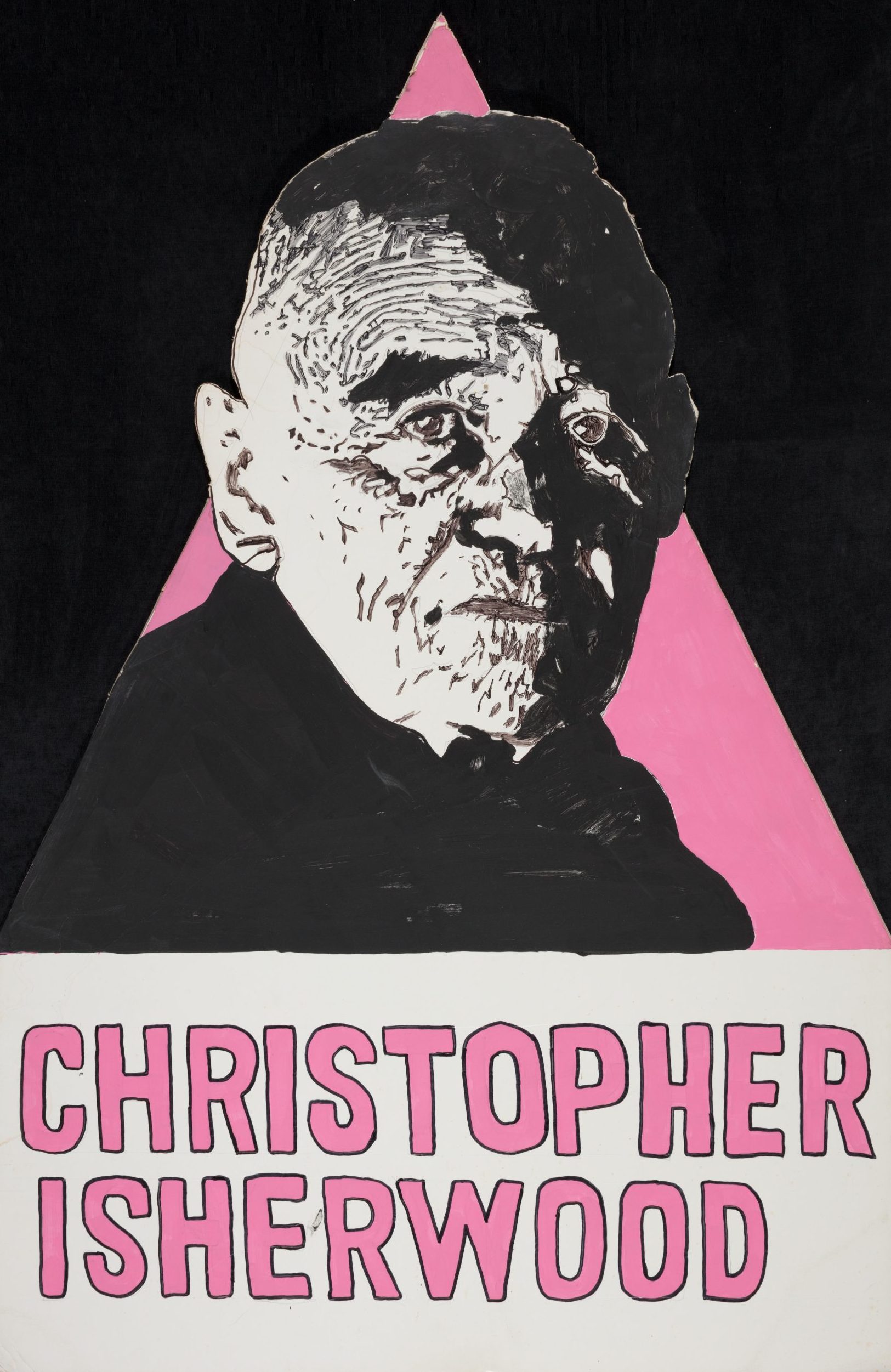

Image 1: ACT UP Los Angeles, “Poster featuring Christopher Isherwood,” June 1989. Los Angeles picket sign collection, ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

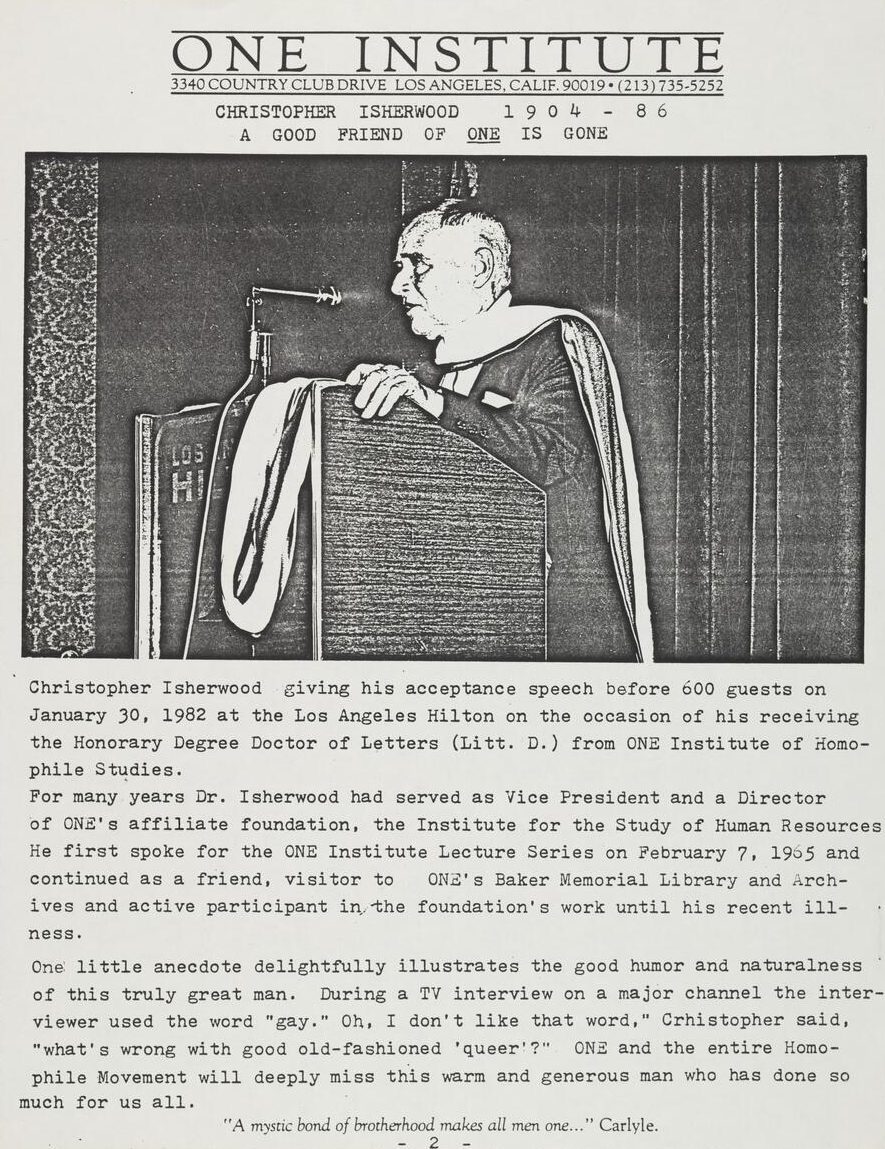

Image 2: ONE Institute, “Christopher Isherwood giving his acceptance speech on the occasion of receiving his honorary doctorate,” January 1982. ONE Subject Files collection, ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy’s Romance

Writer Christopher Isherwood and painter Don Bachardy met on the beach in 1952, launching a life-long partnership. Isherwood’s 1964 novel A Single Man memorialized the beach and Santa Monica Canyon’s gay culture in modern literature, describing gay beachgoers in 1946 as “dancing to the radio, coupling without shame on the sand.” Isherwood moved to the Canyon in 1939 on the heels of his mentor, the British-American philosopher Gerald Heard. Bachardy began visiting the beach in 1948, taking rides there on the streetcar with his gay brother Ted– “because that was the queer beach” – where Ted often would meet lovers. On Valentine’s Day, 1953, after a trip to Ginger Rogers, Bachardy decided to stay the night with Isherwood and thus a complex, enduring romance began. When discussing this story of beach romance with Bachardy in December 2010, author David Kipen quipped, “Talk about one of the great unmounted plaques in Los Angeles.”

In January of 1982, Isherwood was awarded an honorary doctorate by the ONE Institute of Homophile Studies, the first accredited institution of higher learning in the United States to offer masters and doctoral degrees in Homophile Studies. He first lectured for ONE in February of 1967, eventually serving as Director of the Institute for the Study of Human Resources, a partner organization to ONE founded by transgender philanthropist Reed Erickson. Isherwood died in 1986, survived by his lover, the renowned portrait artist Bachardy, who still resides in Santa Monica.

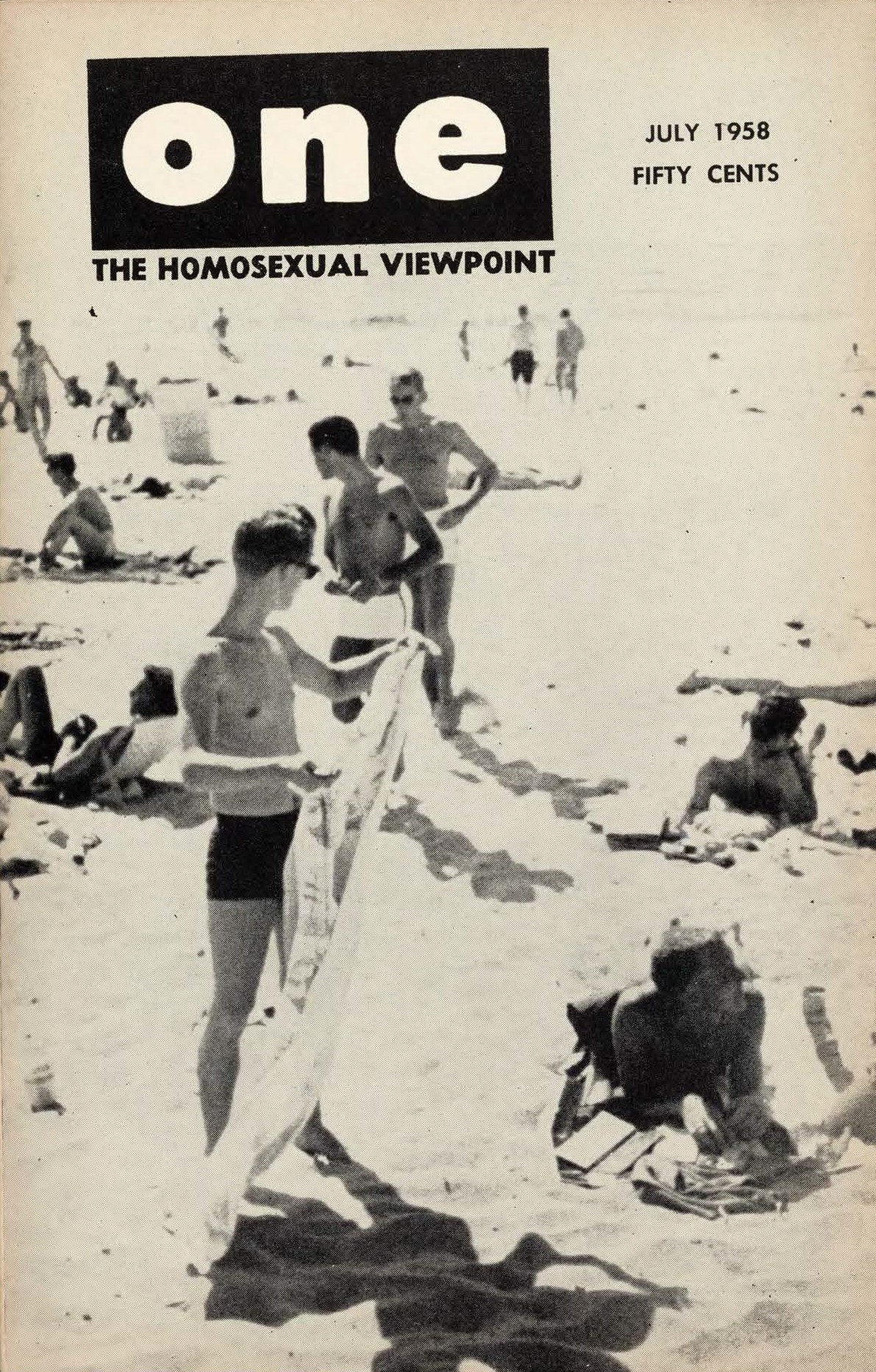

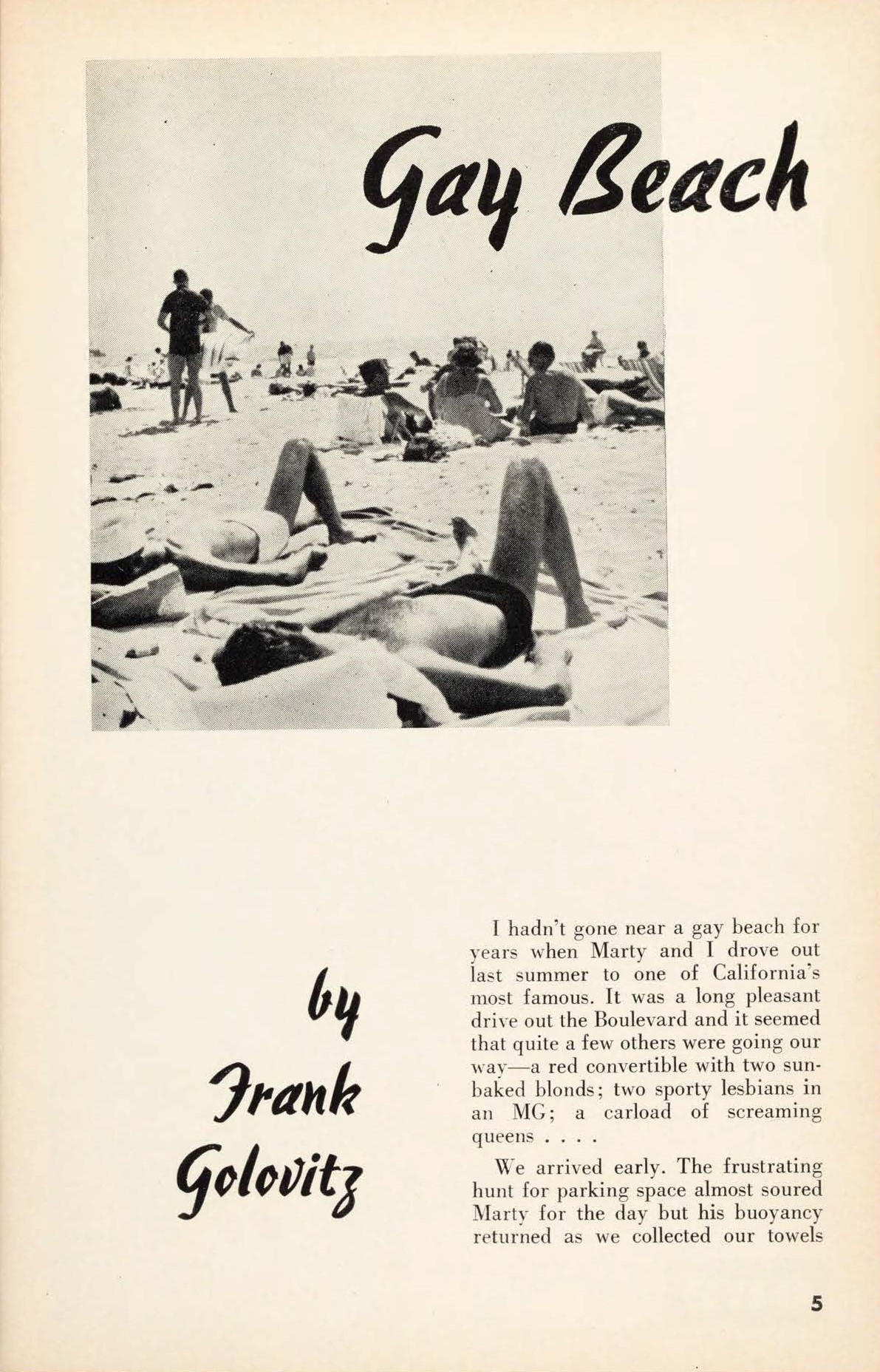

Image: ONE Inc, ONE Magazine, July 1958. Periodicals collection, ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

ONE Magazine

In January 1953, ONE, Inc.— founded by W. Dorr Legg, Jim Kepner, and Don Slater— published the inaugural issue of ONE Magazine, the first widely distributed LGBTQ+ publication in the United States.

The Los Angeles postal authorities seized 1953 and 1954 issues of ONE on charges of obscenity, simply for containing articles, editorials, short stories, book reviews, and letters to the editor from a homosexual perspective.

In 1958, the landmark Supreme Court case, ONE, Inc. v. Olesen, determined that ONE Magazine was not in violation of obscenity laws, becoming the first ruling to deal with homosexuality and the first U.S. Supreme Court case to affirm the free speech rights of LGBTQ+ people.

That same year, Jim Kepner published the article “Gay Beach” in ONE‘s July issue, under the pseudonym “Frank Golovitz.” Reflecting on gay-friendly beaches, including in Santa Monica, Kepner shares an observation from a friend, Marty: “Doesn’t the sight of that crowd thrill you? Right out in the open, hundreds of our people, peacefully enjoying themselves in public. No closed doors, no dim lights, no pretense… I think beaches like this are part of our liberation.“

Kepner further writes about how gay beaches borrowed from community traditions of African Americans who faced segregated public beaches, created space for more class diversity than gay bars, and welcomed gay couples with children.

Freedom from Discrimination

Young gays and lesbians continued to migrate to Los Angeles throughout the 1960s, both taking advantage of and accelerating a sexual and gender revolution. At the start of the 1960s, Los Angeles was home to nearly 150,000 gays and lesbians. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, LGBTQ+ people began taking more public and radical actions to secure their civil rights and transform social norms around gender expression and sexuality, laying the groundwork for a powerful response to AIDS neglect in the 1980s and 1990s.

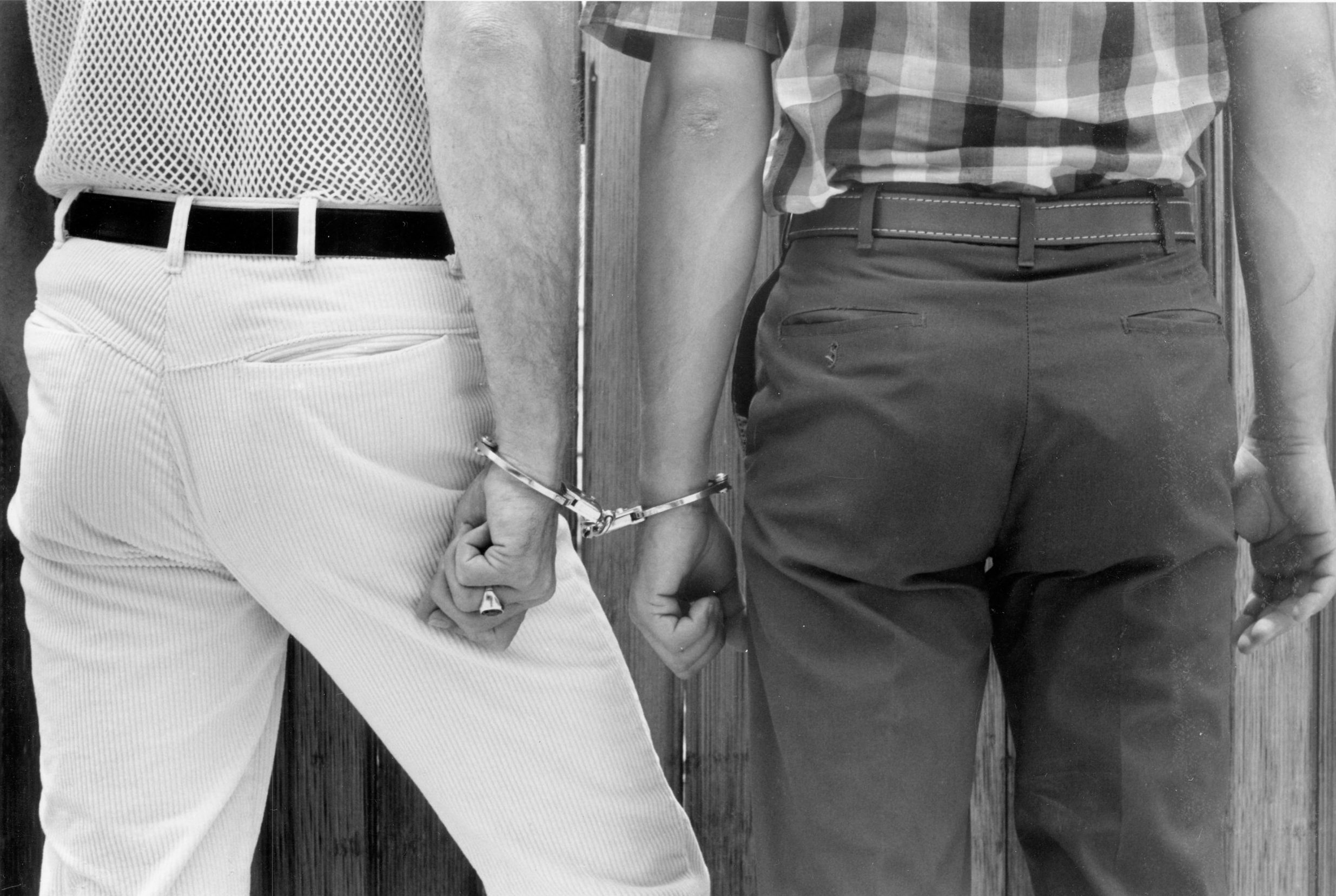

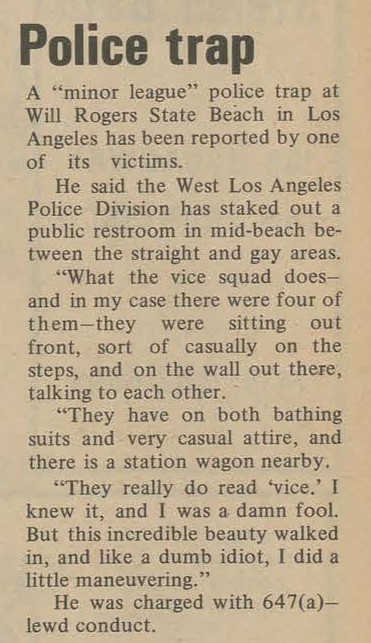

Image: “Police trap,” from The Advocate, July 1970. Periodicals collection, ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

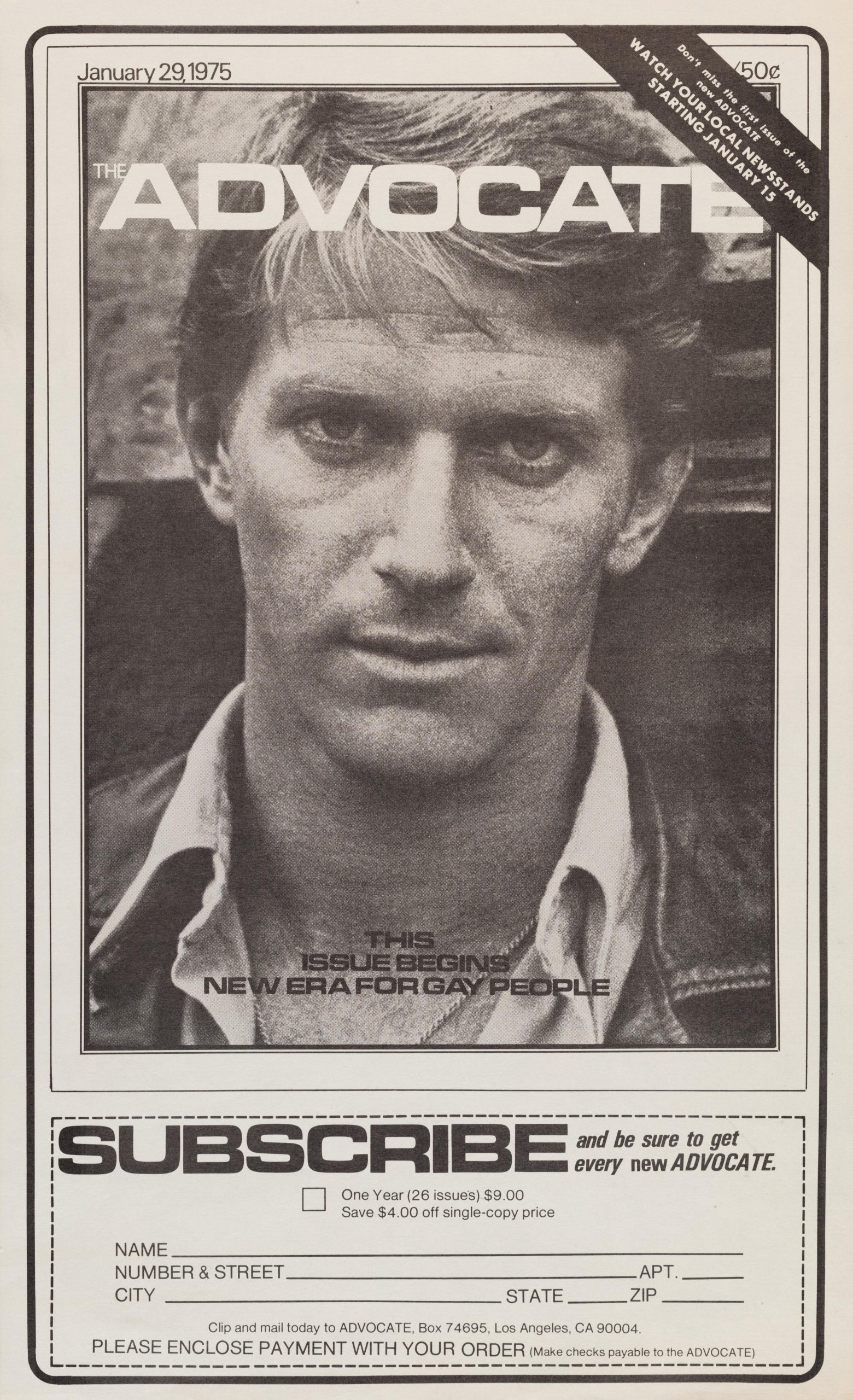

Image: “This Issue Begins a New Era for Gay People,” from The Advocate, January 1975. LGBTQ poster collection, ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

Known in Gay Magazines

Describing the gay beachgoers at Ginger Rogers Beach in 1976, Santa Monica’s Evening Outlook reported: “On weekends, thousands of gay men– most attired in skimpy, clinging bathing suits– gather in groups of two to four in a close cluster along the waterline.” Interviewed by the local paper, lifeguard Herb Thacker noted that popularity of the gay beach had exploded in the early half of the 1970s: “People read about it gay magazines everywhere. It’s known all over the world.” He stated that relations with other groups of beachgoers were mostly calm, despite some fights between gays and surfers– and barring an incident with the police on July 4 of that year.

Image: “Five shirtless men pose at the Santa Monica Gymfest,” William S. Tom, September 1975. Photographs, ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

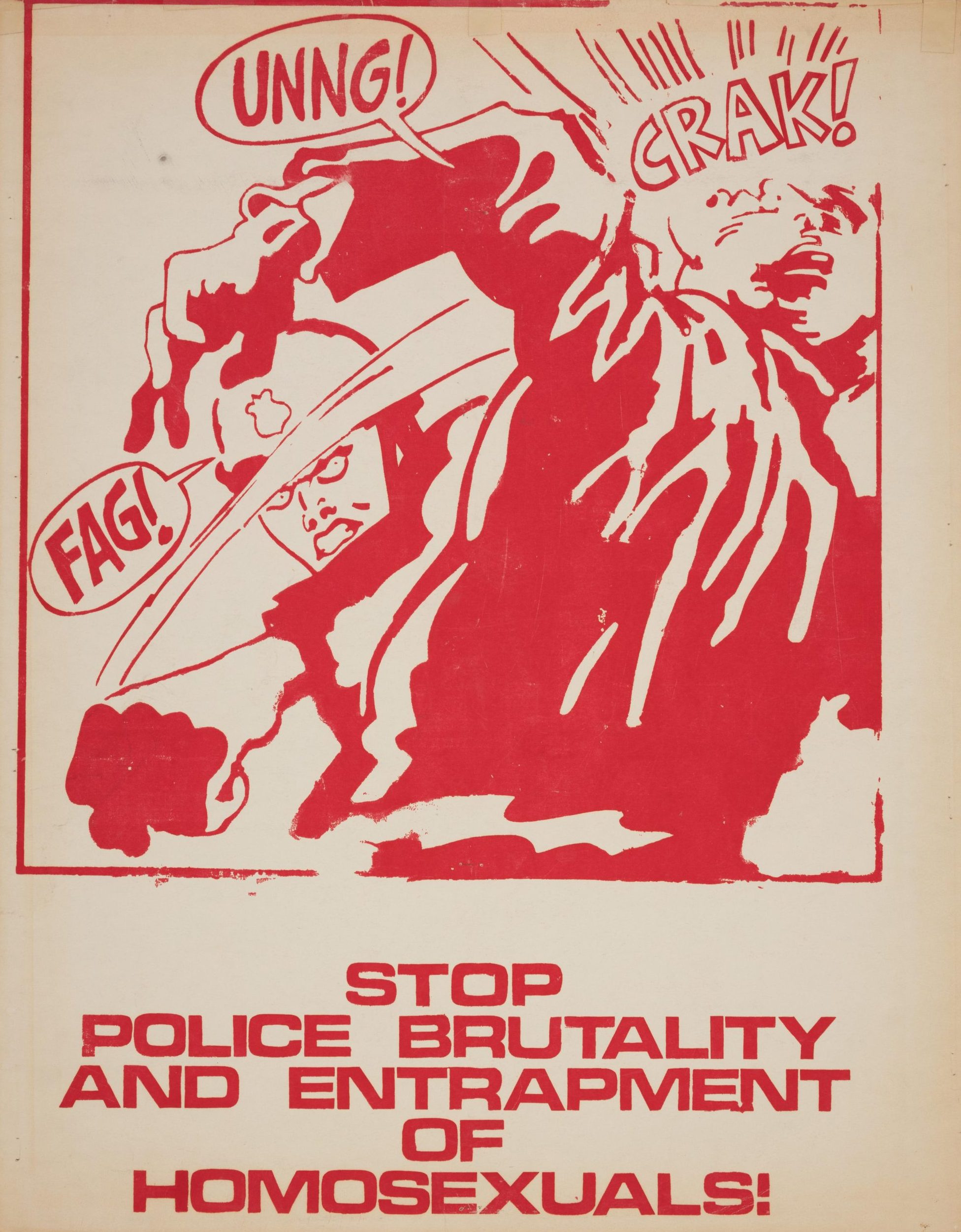

Image: Gay Liberation Front, “Stop Police Brutality and Entrapment of Homosexuals!,” 1971. LGBTQ poster collection, ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

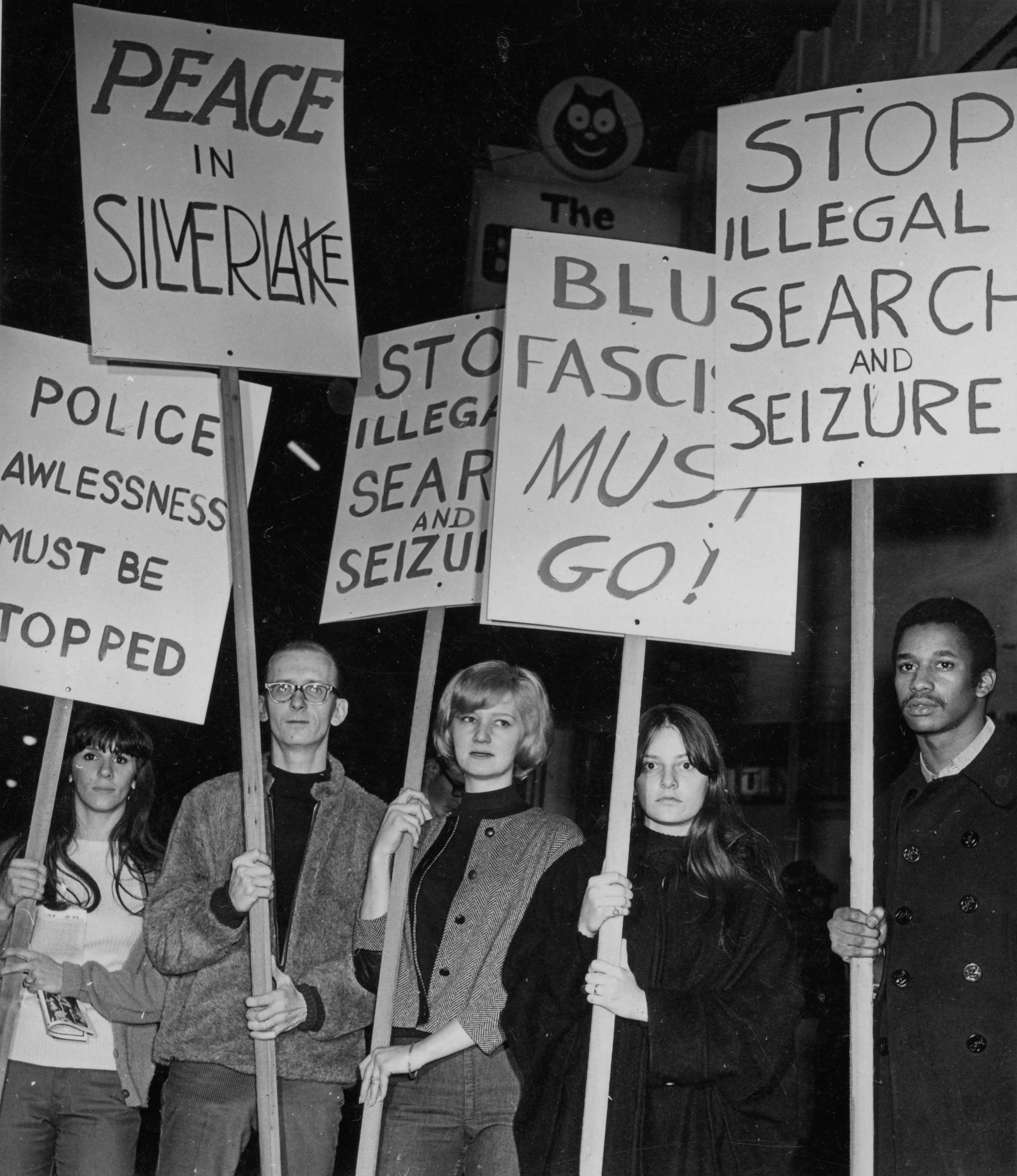

Vice Patrol

Vice patrol began cracking down on queer beachgoers at Will Rogers State Beach as early as the 1950s as reported in Santa Monica’s Evening Outlook. Under the leadership of Chief of Police William Parker– called “Wild Bill Parker” by the gay community– and criminal psychologist Paul de River– who believed that gays presented a danger to children and society, the Los Angeles Police Department doubled down on homosexual behavior and cross-dressing at bars and public spaces in the 1950s and 1960s through a dedicated “vice squad.” Vice squads in Los Angeles were particularly effective compared to other cities because they employed formerly-aspiring Hollywood actors.

Image 1: “‘Anatomy of a raid,’ man (right) arrested for prostitution on Selma Avenue by a plainclothes policeman (left),” from The Advocate, July 1968. Advocate records, ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

Image 2: “Second Gay Liberation Front picket at the Hollywood police station to protest police brutality and entrapment,” from The Advocate, January 1971. Advocate records, ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

Warnings from The Advocate

Vice officers in plain clothing would often “entrap” gay men by inviting or coercing perceived homosexuals to perform intimate or sexual acts at bars or public restrooms; whether these men took the bait or not, the officer would perform an arrest upon any indication of interest. Queer women were often targeted for dancing together at bars or wearing masculine clothing in public. In addition to jail time on felony offenses, it was common for queer people who were arrested to lose their jobs or careers, and to suffer from depression or alcoholism. In 1970, The Advocate– the first national gay newspaper, founded in Los Angeles in 1967– warned its readers of a “minor league” plainclothes vice squad stationed at Will Rogers after a gay man reported being entrapped, arrested, and charged with lewd conduct by the West Los Angeles Police Division. The following month, they again warned readers that arrests continued to be made at this location, describing it as a “hot spot” for being targeted by police.

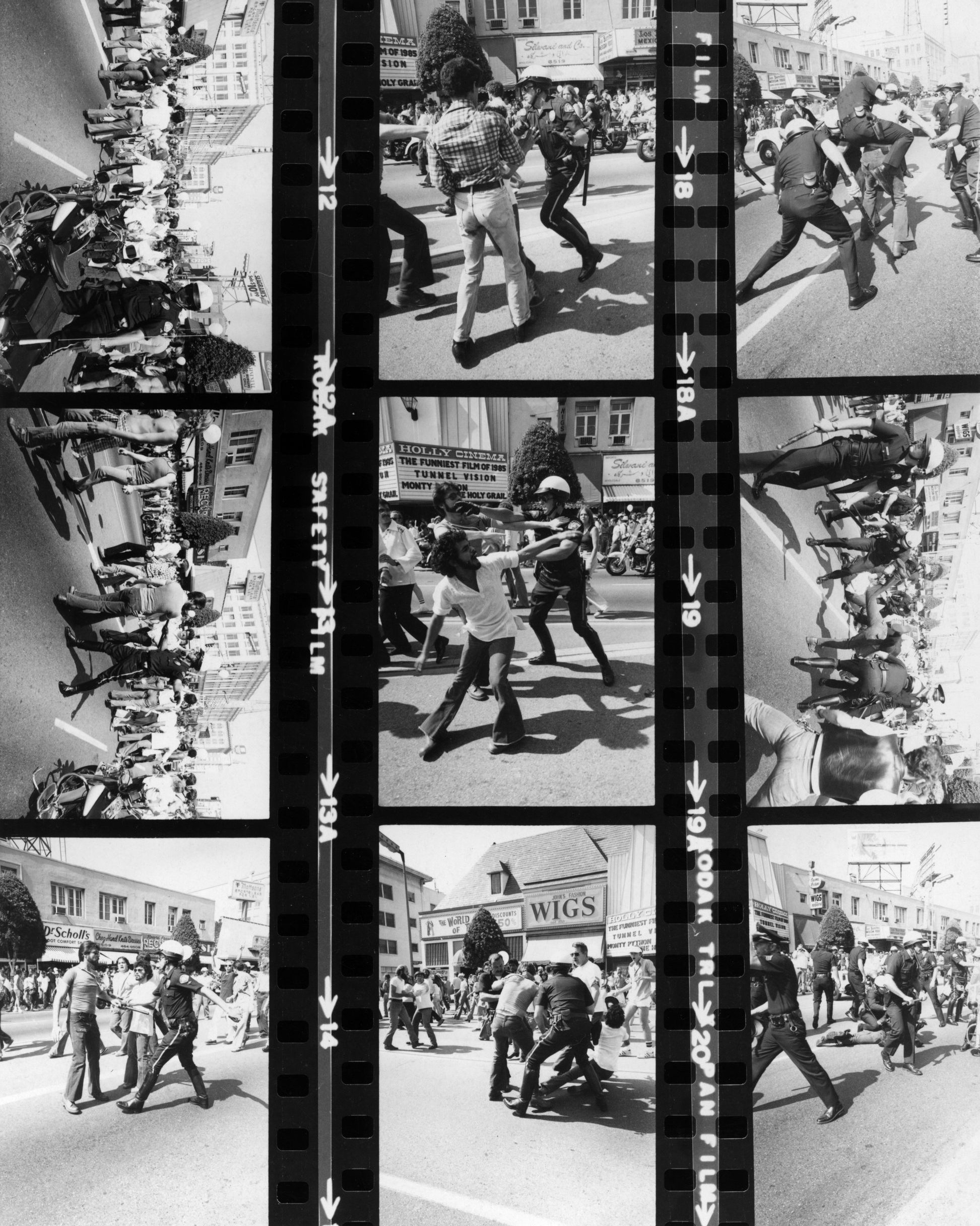

Image 1: Pat Rocco, “Police scuffle with the crowd at the Los Angeles Christopher Street West pride parade,” July 4, 1976. Pat Rocco photographs and papers, ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

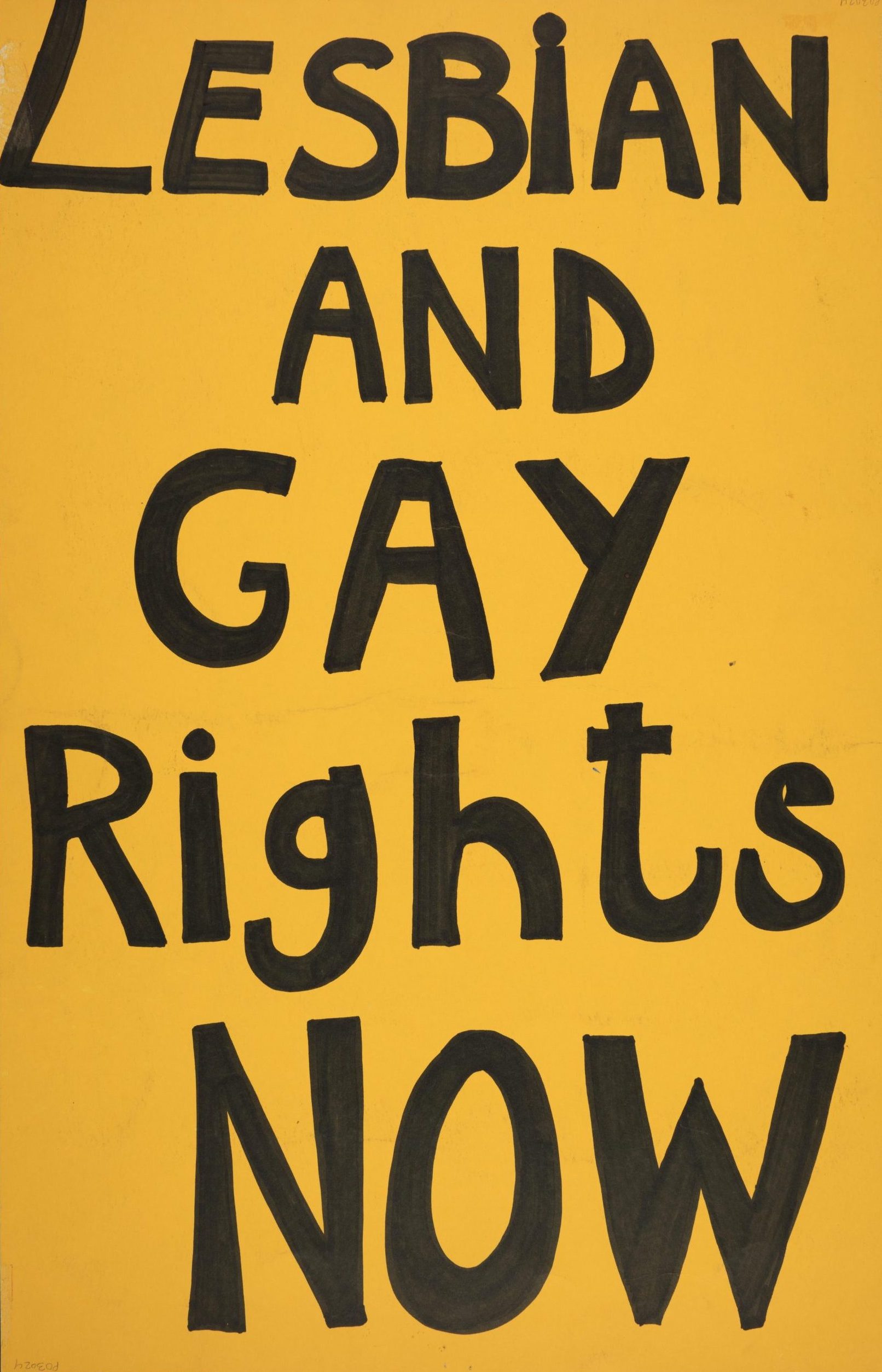

Image 2: “Lesbian and Gay Rights Now,”1976. LGBTQ Poster collection, ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

Image 3: “Mayor Tom Bradley is welcomed by Morris Kight (left), Don Amador (center), and Dick Hingson (right) to the Gay Community Services Center,” 1978. Photographs, ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

Independence Day 1976

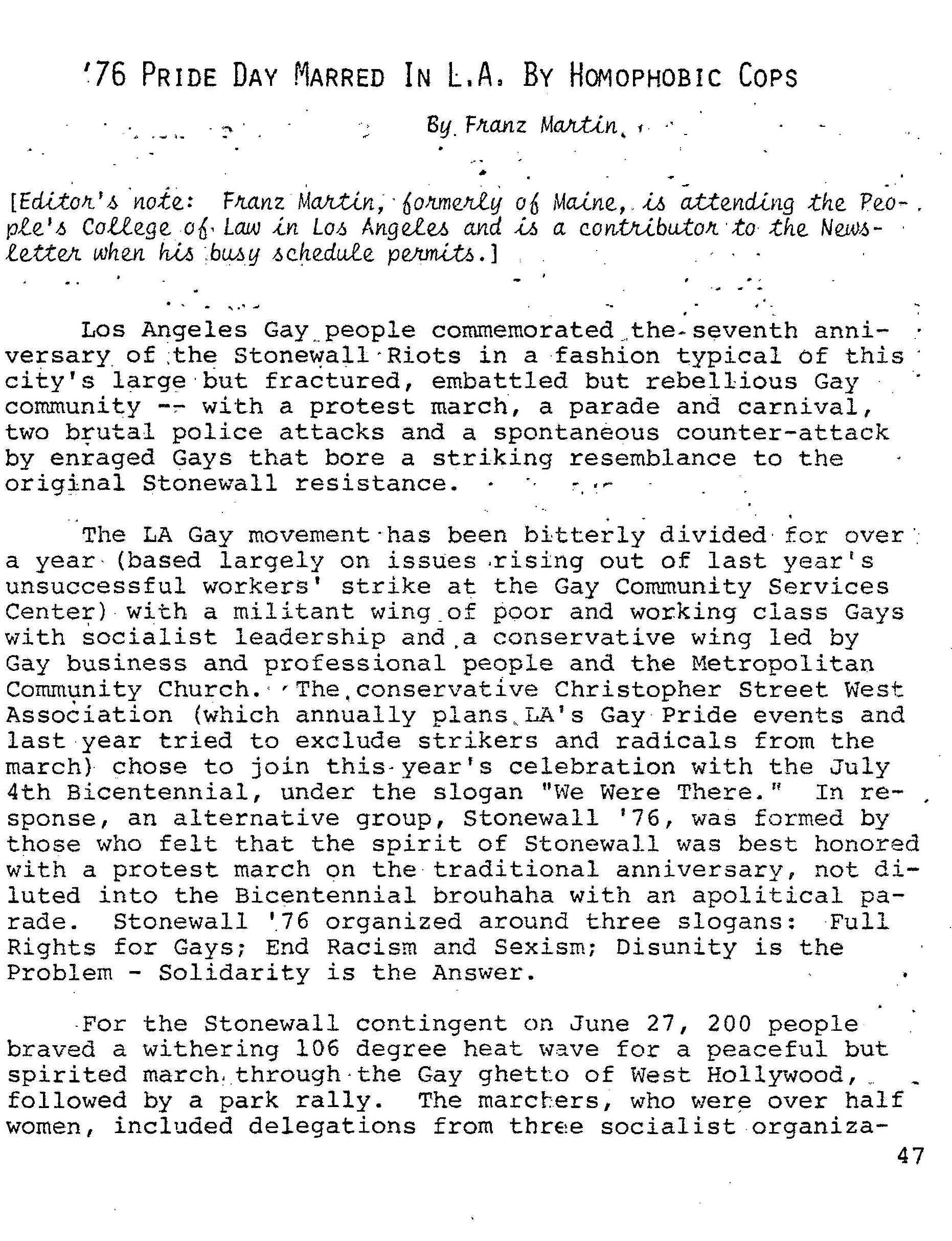

On Independence Day, 1976, queer beachgoers and allies took a stand in the face of police harassment “with a magnificent display of courage and unity.” Reportedly 2000 people were gathered at Will Rogers Beach to celebrate the July 4 holiday. When vice officers pulled two gay men out of the water and began beating them with batons, onlookers fought back, crowding around the officers in an attempt to dissuade them and eventually “pelting the cops with stone, sand, cans, and seaweed.” When one woman attempted to help one of the men beaten by the police, she was thrown to the ground and run over by the police jeep, needing to be hospitalized for leg injuries. The Los Angeles Times reported on the incident, in addition to other local and national publications, noting that several involved suffered minor injuries.

Two years after the incident, Don Amador— an appointed gay community liaison for Mayor Tom Bradley, the first position of its kind in the nation— worked with local elected officials to have homophobic graffiti removed from a structure at Ginger Rogers.

Image: Franz Martin, “’76 Pride Day in Los Angeles Marred by Homophobic Cops,” from the Maine Gay Task Force Newsletter, August 1976. Periodicals collection, ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

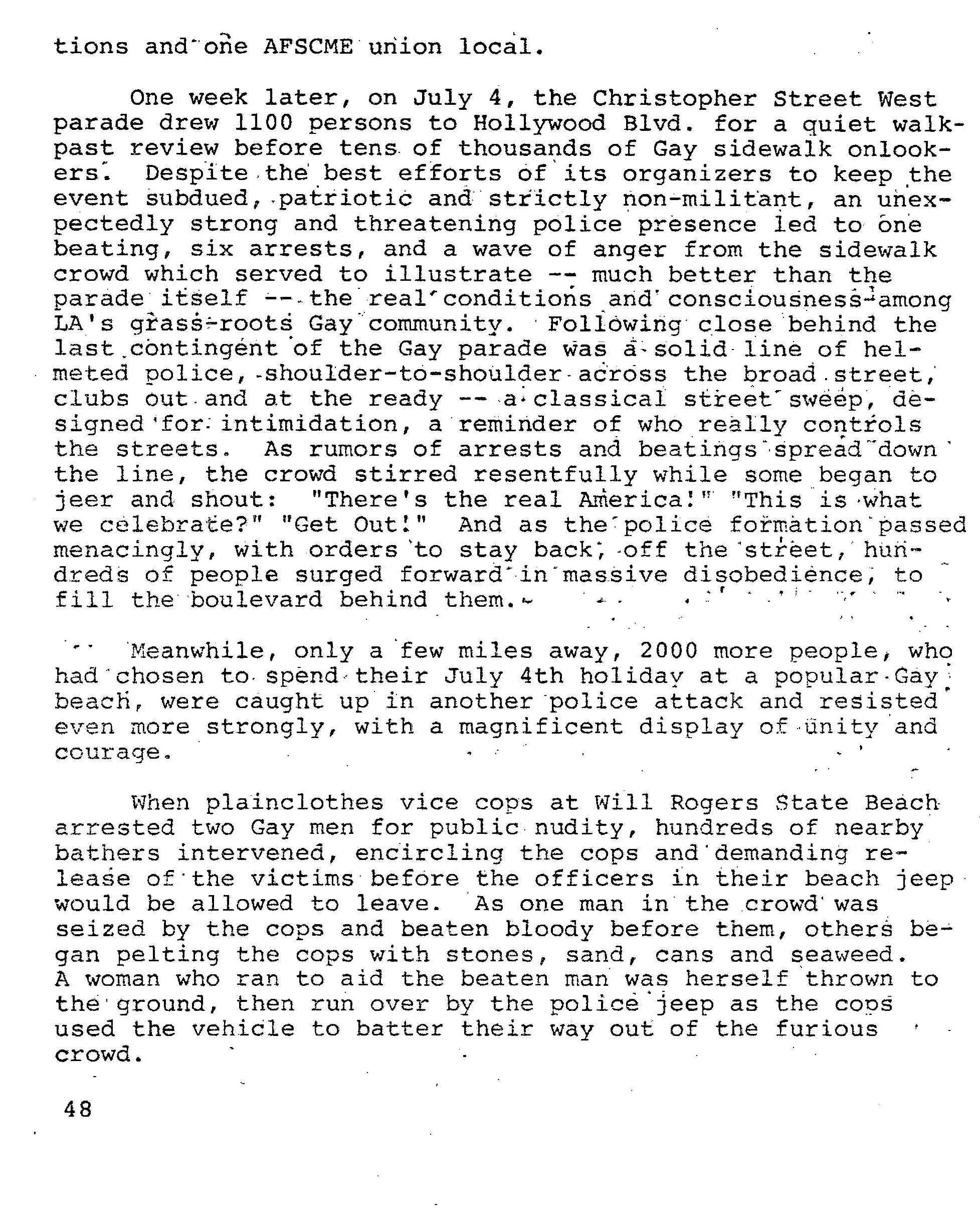

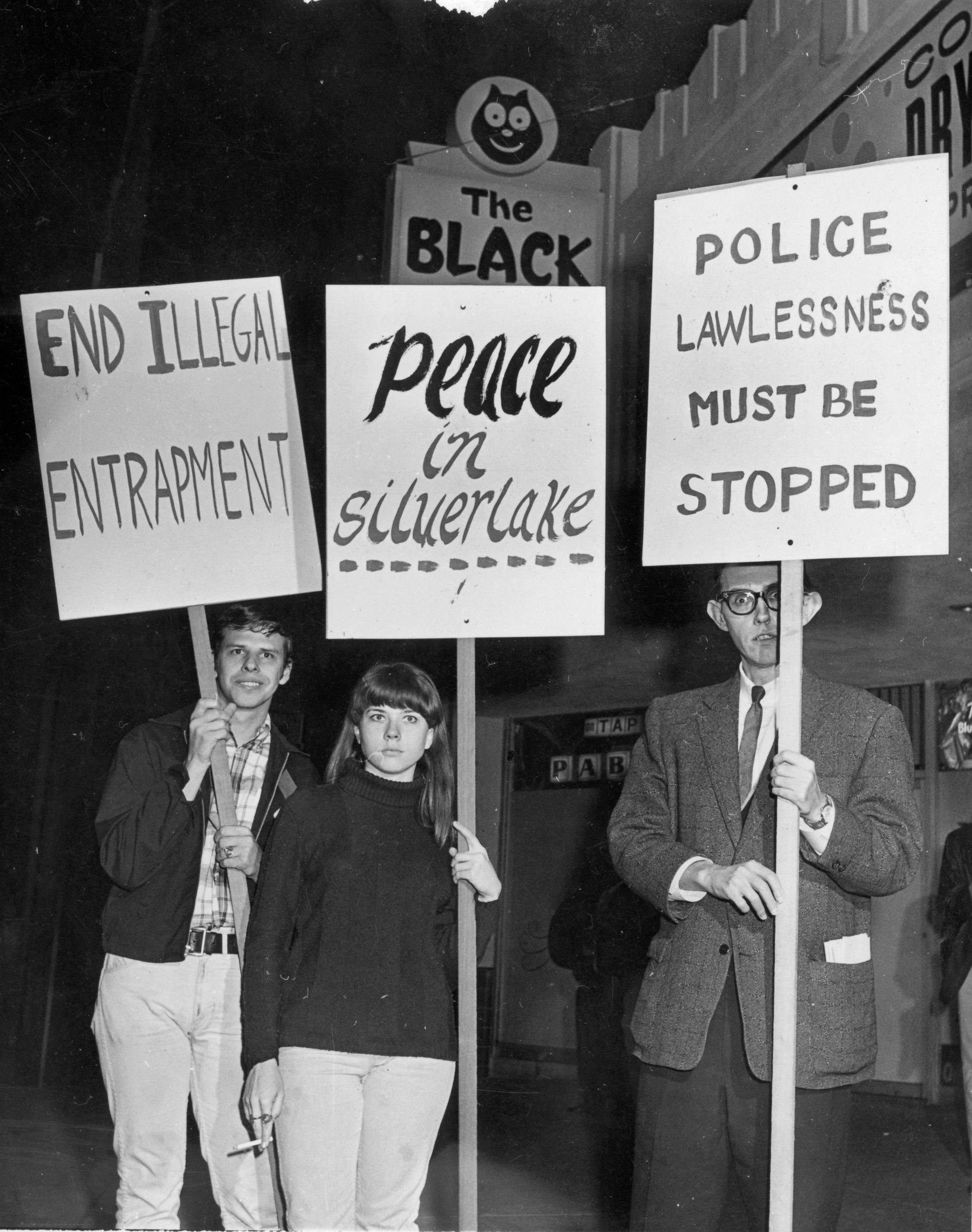

Images: Personal Rights in Defense and Education (PRIDE), “Black Cat demonstration,” February 1967. Advocate records, ONE Archives at USC Libraries.

Queer Resistance

True to the credence of that day’s Independence Day celebration– “that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness”– beachgoers at Ginger Rogers resisted discrimination and asserted their rights. Prior to the Stonewall Riots of 1969 in New York City, queer communities in Los Angeles had already shown a willingness to embrace public demonstrations in the fight for LGBTQ+ civil rights in the Black Cat Protests of 1967. On New Year’s Eve of 1966, police raided the Black Cat while disguised in plainclothes and beat several queer bargoers for exchanging same-sex kisses at the stroke of midnight. On February 11, 1967, over 200 LGBT patrons picketed and gave speeches in a protest of police discrimination against queer people in Los Angeles. The Independence Day event at Will Rogers represented another key moment in this struggle for freedom and dignity.

Image 1: Kent Garvey, “Community Youth Education Project in the Christopher Street West pride parade,” June 1983. Kent Garvey photographs, ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

Image 2: “Frontrunners Track Club at the Christopher Street West pride parade,” June 1982. Christopher Street West Association collection, ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

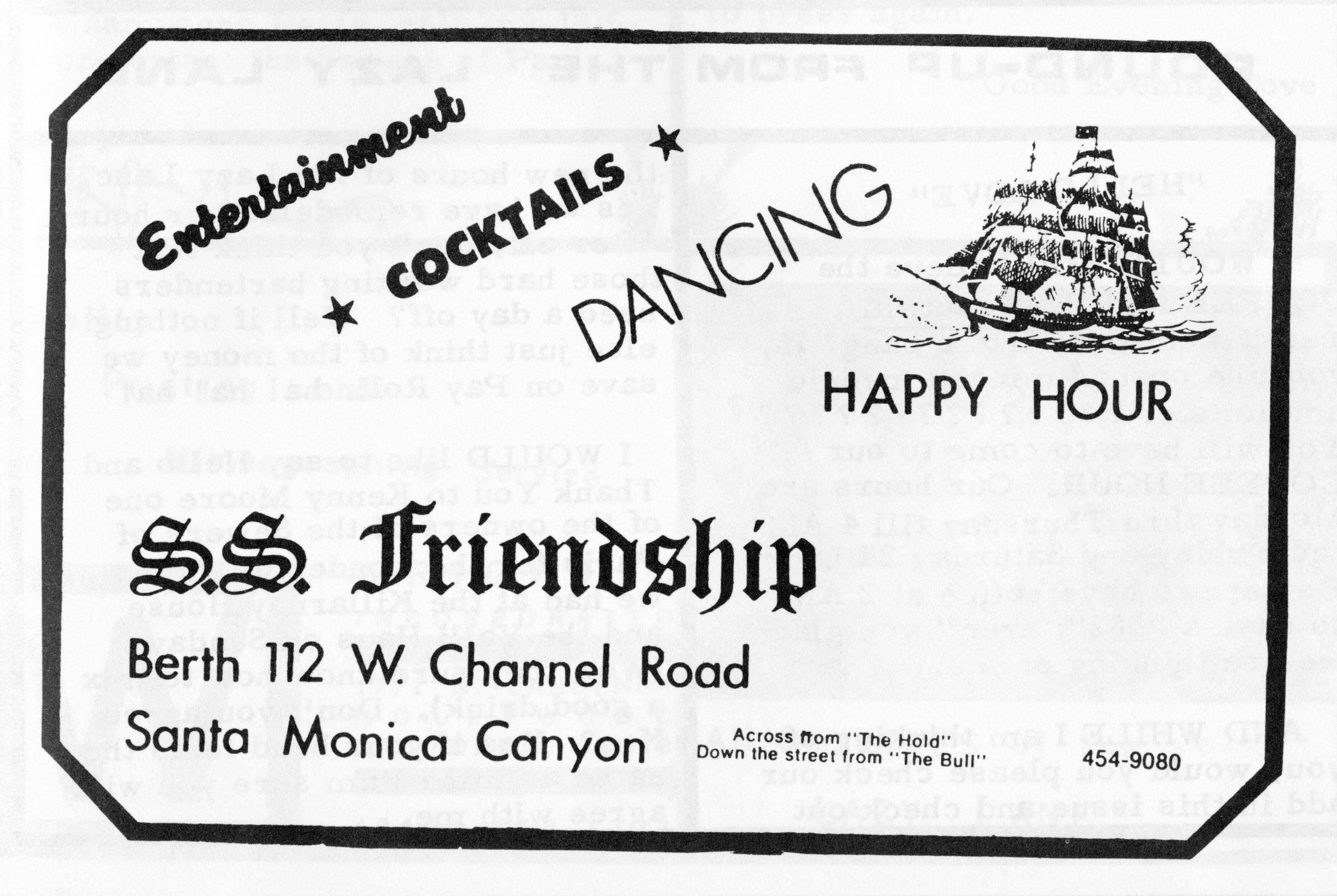

Image 3: “S.S. Friendship advertisement,” from The Voice, 1968. Periodicals collection, ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

Fundraising and Social Events

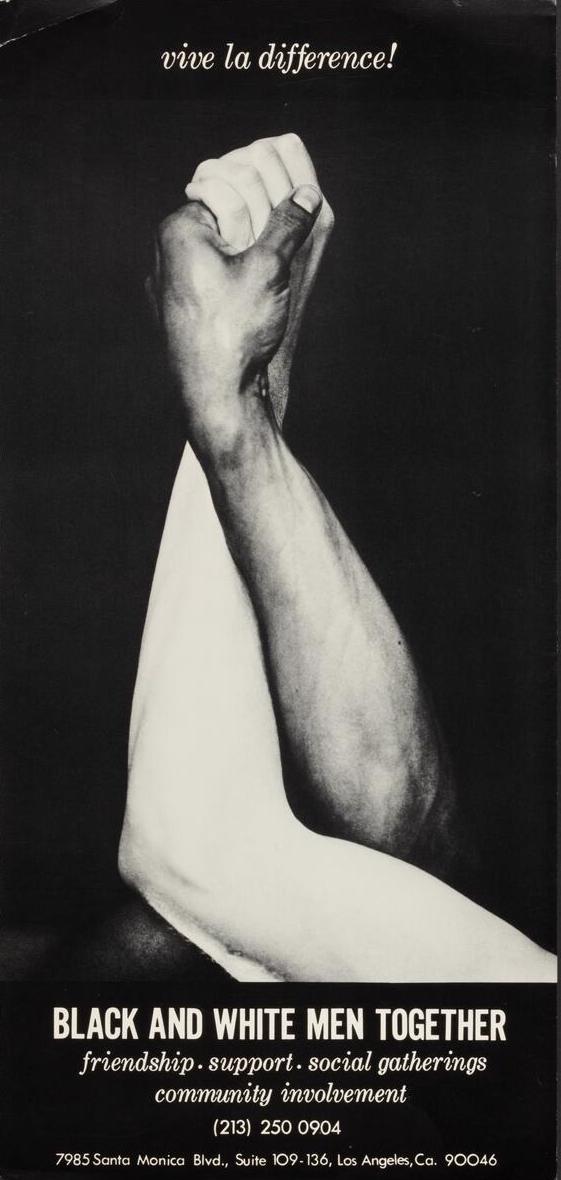

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, LGBTQ+ organizations held social and fundraising events at the beach. In 1983, the Frontrunners– an LGBTQ+ running club that fundraised for people living with AIDS– hosted a “Fun Run & Bike Ride” event at the beach. In 1985, the Community Youth Education Program organized a party and fundraiser at the beach for queer youth 23 and under. CYEP– as part of the ONE Institute– was founded in 1982 to support youth with navigating queer identity, family, and school while advocating for LGBTQ+ issues and history through public programs. In 1992, Los Angeles Black and White Men Together– a group that organized in the 1980s to challenge racism and homophobia– held a beach party at Will Rogers.

Opened in 1937 and located across from the queer beach at the entrance of Santa Monica Canyon, the S.S. Friendship also played a key role in fundraising and providing space for community causes for decades. In February of 1981, the Friendship held an event to raise funds for the Gay and Lesbian Community Services Center, founded in 1972, as federal funding was ending. In June of 1984, the S.S. Friendship organized a show night called “Summer Nite’s Cruise” to provide financial support to people living with AIDS. In July of 1984, the Southern California Gay Bartenders Association held a meeting there. The Friendship bar was sold in 2005, and reopened under a new name, maintaining the same ship’s bow entrance.

Image: Black and White Men Together Los Angeles, “Vive la difference!,” undated. LGBTQ Poster collection, ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

West Coast’s Statue of Liberty

By the 1990s, Ginger Rogers Beach had solidified its status as a place of liberation for queer people. In 1995, Christina DiEdoardo of San Diego’s Gay and Lesbian Times would write, “Will Rogers claimed he never met a man he didn’t like. Whether you’ll agree with this assessment of the crowd at Will Rogers’ State Beach depends on your taste. It’s a mixed crowd of both gay and straight patrons.” She characterizes Southern California’s beaches, including Ginger Rogers, as the “West Coast’s answer to the Statue of Liberty,” which “serve as a symbol of hope and a brighter future.”

Pride Month 2023

For Pride Month 2023, One Institute joins Los Angeles County Supervisor Lindsey Horvath, Los Angeles County Fire Department Foundation, and Los Angeles County Fire Department-Lifeguard Division in commemorating the vibrant queer history of Ginger Rogers Beach. With lifeguard towers now bearing the colors of the Progress Pride Flag, painted by queer artist Kat Bing, there are many more past stories to be told and future memories to be made at this historic place.

Towers Vandalized

In the two days following the unveiling of the painted towers and historical markers at Ginger Rogers Beach, the towers were vandalized. The windows were smashed, interpretive signs stolen, and walls marked with anti-Semitic and anti-LGBTQ slurs. The tower at the main part of the gay beach was repainted in Progress Pride Flag colors by artist Kat Bing while the other tower was returned to its original blue color. A new, larger historical marker was installed on the Pride tower in summer 2024. The incident was briefly investigated as a hate crime by the Los Angeles Police Department but ended inconclusively. This followed a similar incident in March 2021, when a rainbow lifeguard tower in Long Beach, dedicated to the local LGBTQ+ community in June 2020, was burned to the ground. In January 2025, the surrounding community of Pacific Palisades faced devastating destruction from wildfires, yet the tower remains standing as a symbol of joy and resilience.

Image: “Ginger Rogers beach tower in the immediate aftermath of the Pacific Palisades wildfires,” January 2025. Courtesy of the Office of Supervisor Lindsey Horvath, Third District, Los Angeles County.

Ginger Rogers Beach: Place of LGBTQ+ Expression and Organizing since 1940s is produced by One Institute as part of its observance of Pride Month 2023. Special thanks to the Office of Los Angeles County Supervisor Lindsey Horvath, Third District, for collaboration on this project, and Lillian Faderman for contributing historical expertise. Research and curation by Trevor Ladner, Director of Education Programs.

Help us sustain exhibitions and programs such as this by making a donation.

For inquiries related to press or media, please email Sadie Buerker, Communications Manager, at [email protected].

In the Press

- “How Queer People Reinvented the Beach,” Michael Waters, them

- “LA County Recognizes Ginger Rogers Beach During Pride Month Celebrations,” Mario Ramirez, FOX 11 Los Angeles

- “Horvath, Zbur Unveil Progress Pride Lifeguard Towers,” Los Angeles Blade

- “Ginger Rogers Beach Gets 2 Pride-Painted Lifeguard Towers,” Phillip Zonkel, Q Voice News

- “Vandals Defaced LGBTQ+ Tributes at Iconic California Beach,” Christopher Wiggins, The Advocate

- “At LA’s Unofficial Gay Beach, Vandals Defaced Lifeguard Towers Painted in Progress Pride Colors,” Caitlin Hernández, LAist

Sources

“Beach Party,” Los Angeles Black & White Men Together Newsletter (1992). Periodicals collection, ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

“Christopher Isherwood’s Los Angeles,” Zocalo Public Square (Dec. 10, 2010).

DiEdoardo, Chris. “Beach Blanket Babylon,” Gay and Lesbian Times (August 17, 1995). Gale Archives of Gender and Sexuality.

Dotinga, Randy. “The ‘Mother of Lesbian History’ Looks Back– and Forward,” Voice of San Diego (July 16, 2021).

Faderman, Lillian and Timmons, Stuart. Gay L.A.: A History of Sexual Outlaws, Power Politics, and Lipstick Lesbians (2006).

“Fundraising Report,” Aid for A.I.D.S. (June 1984). Morris Knight Papers and Photographs, ONE Archives at USC Libraries.

Funk, Mason. “Interview with Don Bachardy,” The OUTWORDS Archive (Apr. 4, 2017).

Gambone, Phil. “Don Bachardy and his Biggest Fan,” The Gay & Lesbian Review (Nov. 2011).

Gutierrez-Jaime, Nisha. “Long Beach’s colorful pride lifeguard tower burned down to the sand,” KTLA5 (March 23, 2021).

Harmon, Andrew. “My Ritual: Boys’ Club,” from “Beach Rituals,” Los Angeles Magazine (July 2010).

Hay, Harry. “Birth of a Consciousness,” The Harvard Gay & Lesbian Review (Winter 1995).

Hay, Harry. “Remarks on Rudi’s Passing” (April 21, 1985). Jim Kepner papers, ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

Hernandez, Caitlin. “At LA’s Unofficial Gay Beach, Vandals Defaced Lifeguard Towers Painted In Progress Pride Colors,” LAist (June 21, 2023).

IGLA Bulletin (Summer 1984). International Gay and Lesbian Archives records, ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

Isherwood, Christopher. A Single Man (1964).

“Jose Sarria,” National Parks Service (accessed May 2023).

Kepner, Jim. My First 75 Years of Gay Liberation (1976). Jim Kepner papers, ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

L.A. AIDS Project, 1983-1985. National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Records, Cornell University Library, Gale Archives of Gender and Sexuality.

“L.A. Calendar,” The Lesbian News (1983). Gale Archives of Gender and Sexuality.

Ladner, Trevor. “Interview with Lillian Faderman,” One Institute (April 24, 2023).

Loughery, John. The Other Side of Silence (1998).

Luckenbill, Dan. “Los Angeles,” GLBTQ Encyclopedia (2006).

Lugowski, David. “Ginger Rogers and Gay Men?: Film Studies, Richard Dyer, and Diva Worship” from Screening Genders: The American Science Fiction Film, pgs. 102-110 (2008).

Lvovsky, Anna. Vice Patrol (2021).

Maine Gay Task Force Newsletter (Aug. 1976). Periodicals collection, ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

Nash, Paul. “Ceta Replacement,” Update (Mar 6, 1981). Gale Archives of Sexuality and Gender.

Nash, Paul. “Liaison Completes One Year on the Job,” Coast to Coast Times (Oct 25, 1978). Periodicals collection, ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

“News Section,” The Lesbian News (1985). Gale Archives of Gender and Sexuality.

ONE Calendar (Feb. 1986). ONE Incorporated records, ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

“ONE, Inc.,” Library of Congress (accessed May 2023).

ONE Letter (April 1985). ONE Incorporated records, ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

“Parks, Tearooms Hotspots,” The Advocate (August 1970). Periodicals collection, ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

“Police Trap,” The Advocate (July 1970). Periodicals collection, ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

“Santa Monica Beach Draws Big Crowd,” Venice-Marina News, reprinted from the Evening Outlook (Sep. 16, 1976). newspapers.com.

“Southland Weather,” L.A. Times (July 5, 1976). newspapers.com.

“Suzy Sez!,” Compass (April 1987). Periodicals collection, ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

“The Black Cat,” ONE Archives at the USC Libraries (accessed June 2023).

White, C. Todd. Pre-Gay L.A.: A Social History of the Movement for Homosexual Rights (2009).

“Youth Project Looks at Today’s Concerns,” Update (Dec. 25, 1985). Periodicals collection, ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

“3 Seized in Nude Bathing Incident,” Evening Outlook (July 5, 1976). Santa Monica Public Library.