The Falling Dream: Unreason and Enchantment in the Gay Liberation Movement

This article is authored by Abram J. Lewis, from the 2018-19 cohort of the LGBTQ Research Fellowship program at the One Institute.

My book project, The Falling Dream: Unreason and Enchantment in the Mad-Queer 1970s is a study of madness and magic in post-Stonewall queer and feminist activism. Traditionally, historians have viewed the 1970s as a decade of decline for political radicalism, however, my research traces a proliferation of unusual activist experiments during these years. I examine communities that turned to things like levitation demos, spells and hexings, spirit channeling, extraterrestrials, and other paranormal forces as resources for political change. I also chart activists’ enthusiasm during these years for nonrational threshold states, achieved variously through drugs, dreams, mysticism, transcendent sex, or simply “going crazy.” Collectively, these strategies all shared a refusal of modernist regimes of secular rationality. These elements were strikingly widespread in 1970s radicalism—although people are sometimes surprised to hear that I can fill an entire book with queer magic and madness. One reason these tactics haven’t attracted attention from historians is that they were simply extraordinarily “far out’—they don’t look much like viable or respectable activism.

In my book however, I argue that these strategies were not just quirky or idiosyncratic, they can be understood as a systemic response to post-Civil Rights political retrenchment. The 1970s saw the foreclosure of conventional approaches to radical activism on many levels, including state repression of activist factions, national backlash against Civil Rights gains, and initial attacks on the Keynesian welfare state that set the stage for neoliberalism’s ascendance in the 1980s. Within this context, refusing secular and rationalist epistemes opened up unexpected new possibilities for pursuing politics otherwise—during an intensely debilitating time. These strategies, for instance, circumvented the need for a large organized base, access to material resources, or palatable reform platforms. I argue, moreover, that challenges to secularism and reason became especially key to early intersectional activism. Specifically, I trace madness and magic through 1970s women of color feminism and queer of color politics, trans activism, and queer organizing around disability (especially psychiatric diversity). All these communities were excluded not just from statist forms of civic engagement, but also from major reform movements of their time. For these communities, madness and magic became resources for engendering altogether different approaches to political work, ones that countermanded liberal ideals of representation, visibility, and civil rights. Inasmuch as neoliberalism is, in a basic way, a regime of debilitation, the oppositional genres of thought and action afforded by unreason and enchantment can by understood as an important site of activist resistance to neoliberalism’s early onset. One of the project’s presentist investments is exploring how these activist traditions can help us think beyond the constrained political imaginary of the so-called “Nonprofit Industrial Complex” today.

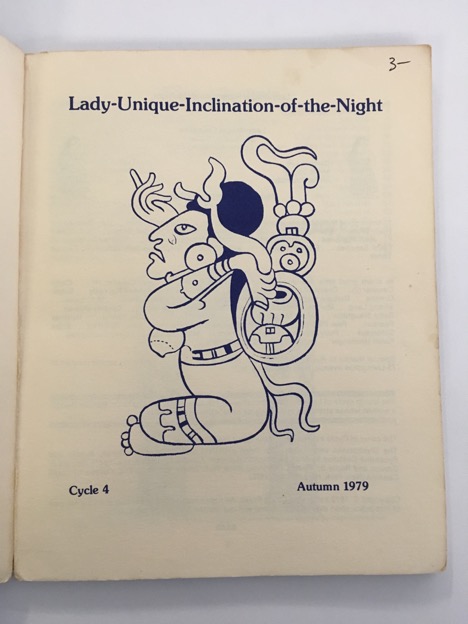

A highlight of the ONE Archives was its holdings around queer solidarity with insane liberation activism in the early 1970s, including organizing around the Atascadero hospital and Vacaville Prison. Additionally, the papers of the notoriously eccentric gay activist leader, Bishop Mikhail Itkin, are useful in documenting the influence of gnostic mysticism on West Coast gay liberation. I was also delighted to find a run of the periodical Lady-Unique-Inclination-of-the-Night—a quasi-academic journal of Goddess feminism that published early work by Audre Lorde, Gloria Anzaldúa, Cheryl Clarke, and others. Often associated with white cultural feminism, Lady-Unique helps establish the importance of witchcraft to 1970s feminist of color thought. Interestingly, in my own research previously, I had found only one other archive with copies of the journal: a community archive without resources to exhaustively process its holdings. But after my initial perusal of the journal at the community archive, the box containing it vanished without a trace, and no staff or volunteers could locate it. Given that I study esotericism and the occult—things that are not supposed to be made public—this was an intriguing development, but nonetheless a research setback. Having now retrieved Lady-Unique, however, I look forward to doing some justice to its contributions, even as I will also do my best to honor the text’s persistent mysteries.

Image Credits

Top image: “Gay Magic is Afoot”, Mikhail Itkin Papers, ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

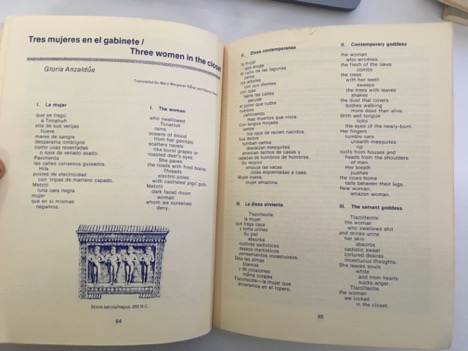

Image 2: Lady-Unique-Inclination of the Night, ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

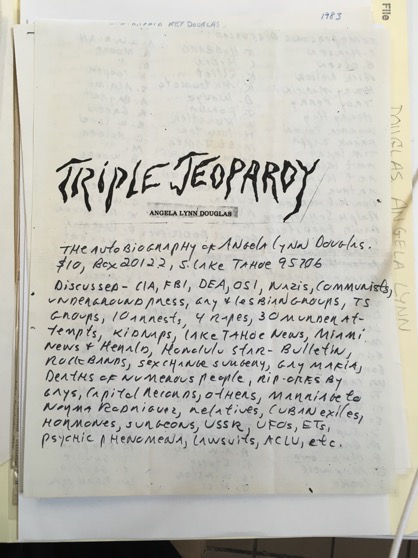

Image 3: Autobiography of 1970s transgender activist Angela Douglas, founder of the Transexual Action Organization.

Image 4: Early contribution by Gloria Anzaldúa to Lady-Unique.

Abram J. Lewis

2018 LGBTQ Research Fellow, One Institute